Toxic Shock Syndrome in the ED

27th January 2021

Meningococcal Septicaemia: The Dangers Of Delayed Diagnosis

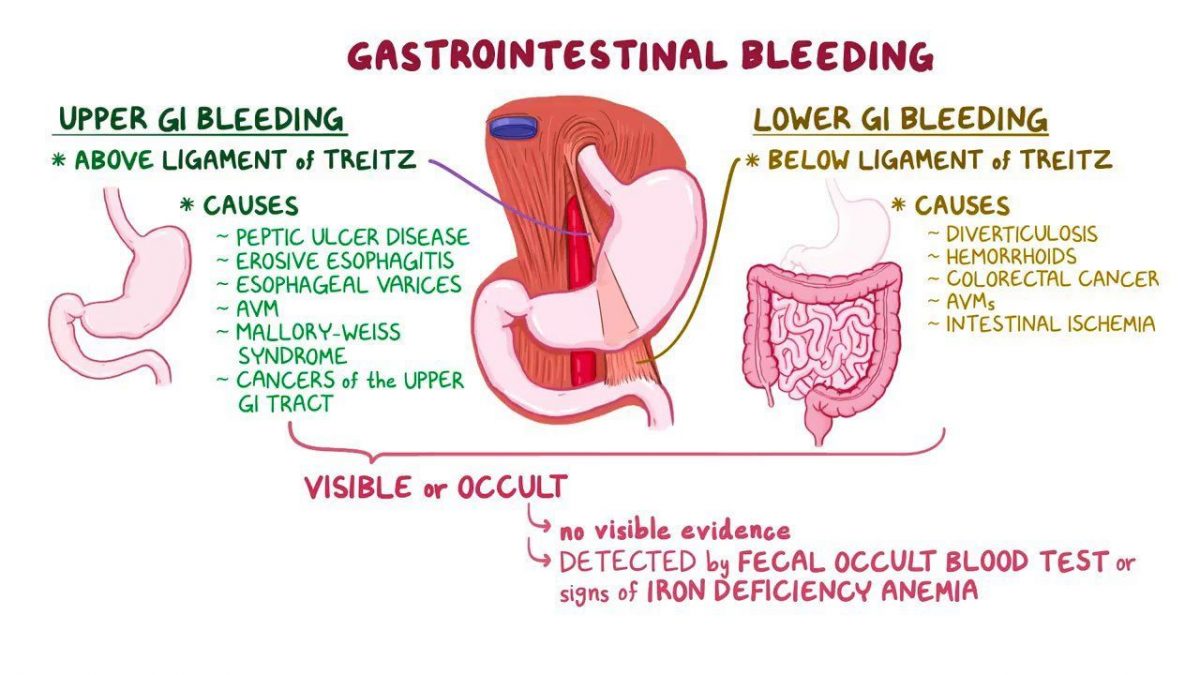

16th February 2021Upper GI bleeding accounts for 50-70,000 cases in the Emergency Department annually. (NICE, 2016) Mortality remains at 10%. Upper GI bleeding covers bleeding from the oral cavity to the ligament of Treitz – the ligament marking the junction between the stomach and the duodenum. Causes of bleeding may include peptic ulcer disease, oesphageal varices, or a Mallory-Weiss tear.

A patient suffering from upper GI bleeding may present with haematoemesis vomiting up blood, or melaena (dark, sticky faeces). Other more general symptoms include: syncope, dizziness, fresh rectal bleeding, hypotension, tachycardia. If the patient haematoemesis, this may vary from a small quantity of blood mixed in vomit or torrential rapid bleeding without any obvious vomitus.

Risk factors must also be accounted for in understanding the severity of GI bleeding: these include a possible Helicobacter pylori infection; known/suspected liver disease; peptic ulcer disease; or alcohol. Peptic ulcer disease accounts for 30% of admitted cases and should be suspected if the patient has high alcohol consumption.

Can a patient with an upper GI bleed be discharged safely?

Before an urgent endoscopy is arranged and treatment is pursued to treat the bleeding, pre-endoscopic tests are necessary to risk stratify the patient’s state and guide subsequent management. Not all patients require urgent care for treating their upper GI bleed and may be discharged safely from the Emergency Department.

The severity of upper GI bleeding controls whether the patient can be discharged safely for out-patient treatment. There are circumstances where this is possible and this requires the use of the Glasgow-Blatchford Score (GBS).

GBS is a well-validated score which consists of 4 components: medical history (hepatic disease, heart failure), symptoms (melaena, syncope), signs (tachycardia, blood pressure), and blood tests (haemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen).

A score of 0 indicates a low-risk patient who, alongside the clinicians judgement, may be safely discharged and an outpatient endoscopy can be arranged as their follow-up. Once the discharged patient undergoes an endoscopy, they may receive oral PPIs. It is important for the Emergency Medicine clinician to follow the current NICE guidelines (2016) advising against prescribing oral PPIs until the patient has had their endoscopy as this has shown to increase re-bleeding risk, mortality and the need for surgery.

If the patient’s score is above 6, there is a 50% increase in the need for intervention, and the Emergency Medicine clinician will refer the patient to the medical team for investigation, admission and treatment.

It is important to note that the GBS cannot be used for lower GI bleeding or for GI bleeding in paediatric patients.

Another risk assessment tool for GI bleeding is the pre-endoscopic Rockall score which can be used to predict health outcomes for the patient. The Rockall score is considered accurate at predicting the mortality risk, but not the risk of re-bleeding which is the major risk if a patient is discharged from the Emergency Department and therefore is of less utility to clinicians in the Emergency Department.

Treating acute upper GI bleeding in admission

In a patient with upper GI bleeding the treatment in the Emergency Department depends on whether the patient is stable or unstable. In a stable patient with normal observations blood tests and the insertion of an IV line may be all the treatment that the patient requires before they are referred specifically for an endoscopy.

If the patient is unstable the normal resuscitation process is required maintaining the airway and breathing while giving fluids. This may require the use of blood and blood products, such as a platelet transfusion, particularly when the bleeding is severe.

Active measures to stop the bleeding may involve either the medical or surgical teams although the primary investigation is by an endoscopist who may be form either or these disciplines and most Emergency Department have access to these in addition to the normal on call specialist teams.

Underestimating the extent of bleeding within the patient may carry dire consequences and the decision to discharge requires not just pre-endoscopic testing, but a full understanding concerning the patient’s entire clinical picture and the use of an appropriate screening tol such as the Glasgow-Blatchford Score (GBS).