Expert Evidence, Independence and Expression: Lessons from John Good v West Bay Insurance plc [2025] SC AIR 70

4th November 2025

Changes over my working life in medicine

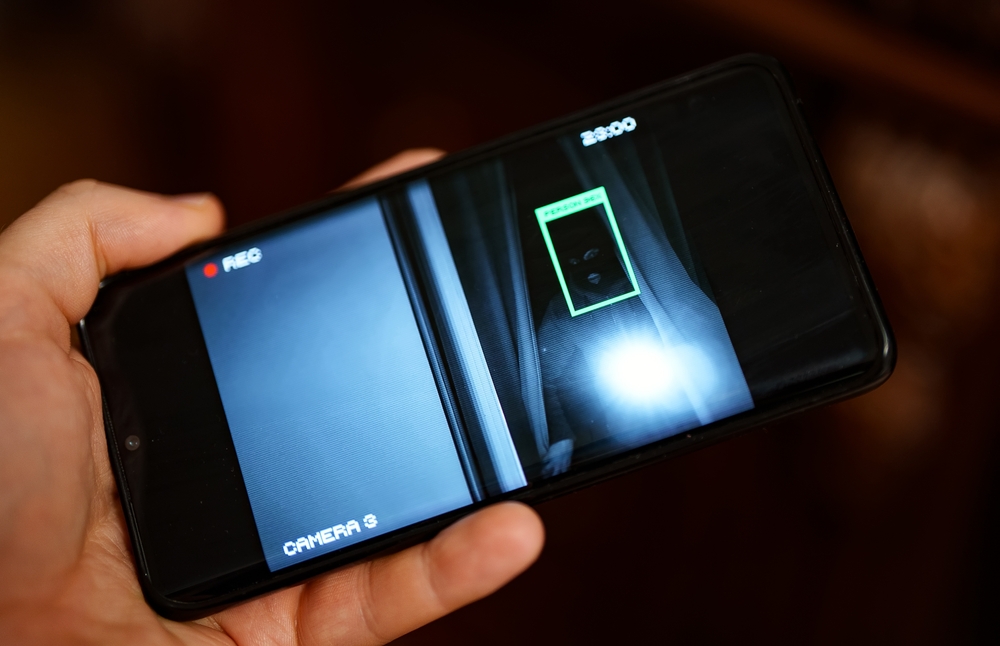

20th November 2025In Perrin v Walsh [2025] EWHC 2536 (KB) the Court addressed serious challenges in the use of covert surveillance. The case is instructive for medico-legal experts because it highlights the importance of reviewing the full evidence record, not just the “headline footage”.

Case summary

The claimant suffered a road-traffic accident where liability was admitted. The defendant commissioned a surveillance firm, The Surveillance Group (TSG), to record covert footage over a two-year period. The edited footage was served to the claimant early in 2025. Subsequently, the claimant challenged the reliability of using the edited surveillance evidence on multiple grounds.

Key issues raised

- The claimant alleged that footage favourable to her case had been omitted or edited out.

- There were gaps in filming, times when surveillance ceased at relevant moments, and logs missing from one operative.

- Some original SD cards, capable of forensic inspection, were not retained.

- The defendants admitted some human error, but argued that the unedited footage remained available, and the edited footage was still probative.

Court’s decision and commentary

The judge accepted that serious shortcomings occurred in the conduct of the surveillance firm and its witness statements. However, the court declined to exclude the surveillance evidence entirely under CPR 32.1. Instead, strict directions were made: the defendant was ordered to serve all unedited footage and to provide detailed witness statements from senior staff at TSG. The experts involved in the case were given a specific warning about the limitations and weight of the surveillance material.

What are the medico-legal implications?

Experts must be aware that surveillance footage may appear compelling, but it may still carry limitations and risks. As the judge said: “surveillance footage cannot definitively show … how much pain [the claimant] is in.”

Here are key points of note for experts in medico-legal work:

- Review all footage and disclosure – Do you have the raw/un-edited material or only an edited version? Gaps matter.

- Check for omissions or editing anomalies – If it seems that the surveillance has been edited, then it could have been edited to support an argument.

- Consider the context – A snapshot in time may not reflect variable conditions (e.g., fluctuating pain, episodic symptoms). The Court emphasised that one recording does not show what happened on another day or at another place.

- Be clear about your role – Experts answer to the court. Determinations of honesty, exaggeration or fundamental dishonesty remain for the trial judge. The expert’s role is to assist with the medical/functional picture in light of all material.

- Flag issues of reliability – If you identify missing footage, editing concerns or retention gaps, you should note these in your report. They may affect how the court and the fact-finder view your opinion.

- Prompt disclosure is critical – The court and commentators emphasise that late disclosure or “ambush” situations may tip the balance away from admitting the footage.

Conclusion

Perrin v Walsh confirms that surveillance evidence remains a powerful tool in personal injury and medico-legal litigation. However, it also reminds us that the provenance, retention and completeness of the material are crucial. For expert witnesses, the directive is clear: you must consider all the disclosed materials, understand what is missing, evaluate the limitations of what is shown, and make clear in your opinion how those factors influence your assessment. In short: never assume the footage tells the whole story.