Necrotising Fasciitis In The ED

19th January 2021

Upper GI Bleeding In the ED

9th February 2021Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS) is a rare but life-threatening toxin-mediated condition caused by bacteria – either Staphylococcus aureus or Group A Streptococcus. These bacteria enter the body and release harmful toxins that trigger a cytokine storm and immune cell proliferation. Consequently, the body enters a state of shock due to a sharp drop in blood pressure, and potentially fatal multi-organ failure results if left untreated.

TSS was initially thought of as mainly menstrual-related due to the correlation between using menstrual products and TSS prevalence. Since a vast improvement in menstrual product manufacturing and education, TSS is now seen in non-menstrual related cases such as skin wounds, burns, or post-surgery.

Staphylococcal TSS typically occurs in localised infections, whereas Streptococcal TSS may result from necrotising fasciitis, bacteraemia, or cellulitis. (Coopersmith et al., 2018)

Recognising Toxic Shock Syndrome

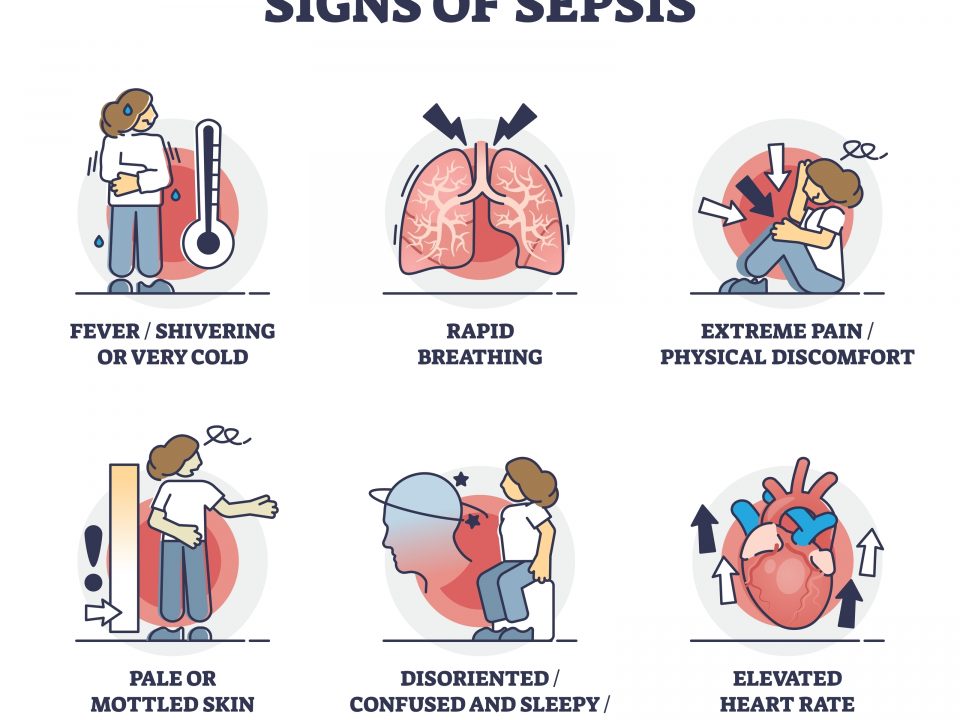

On arrival at the Emergency Department, the patient may present with the following symptoms: high fever, low blood pressure, and a rash with desquamation. If a wound is infected, the patient may experience localised pain in that area. Vomiting and diarrhoea can also present along with nonspecific symptoms, including headaches, malaise, and a sore throat.

If left untreated, the patient’s symptoms will escalate into confusion, septic shock, and multi-organ failure. Multi-organ failure can involve hepatorenal impairment, coagulopathy, and necrosis. Therefore, it is important to at least suspect TSS quickly upon admission.

To diagnose TSS, blood, wound, and fluid tissue should be cultured immediately to ascertain whether Staphylococcal or Streptococcal infection is present. A complete blood count may also reveal thrombocytopenia, hypocalcemia and elevated creatine phosphokinase – all suggestive of the onset of end-organ damage. It is especially vital to perform a lumbar puncture to identify if sepsis has spread to the meninges. These tests will suggest TSS, and the clinician can continue with urgent treatment.

It is important to suspect that if the patient is menstruating and presents with a high fever and emesis, this may indicate early signs of TSS.

Treatment & Management of Toxic Shock Syndrome

TSS requires early action to prevent the patient’s condition from declining further. If TSS is suspected, the patient should receive aggressive IV fluid hydration with crystalloids and vasopressor support (noradrenaline) for refractory hypotension. Fluid resuscitation is essential to combat leaky capillaries and reverse hypotension.

Clinicians must also administer broad-spectrum antibiotics if TSS is suspected. This will involve a combination of clindamycin + either vancomycin, a carbapenem, or penicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor. If Staphylococcal TSS is suspected, clindamycin plus vancomycin is recommended. A standard antibiotic course will last 14 days. Further antibiotic use is advised if TSS remains highly resistant.

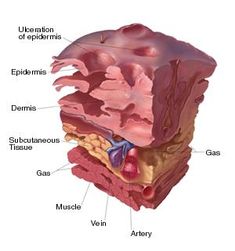

If necrotising fasciitis is a suspected cause of TSS in the patient, damaged soft tissue should be managed effectively via surgical debridement. If menstrual TSS is suspected, ensure that menstrual products are removed.

The patient must be transferred to ICU upon management initiation.

In ICU, the patient must undergo stress ulcer and DVT prophylaxis via H2-antagonists or proton pump inhibitors, and heparin or low-molecular weight heparin with compression stockings, respectively.